|

|

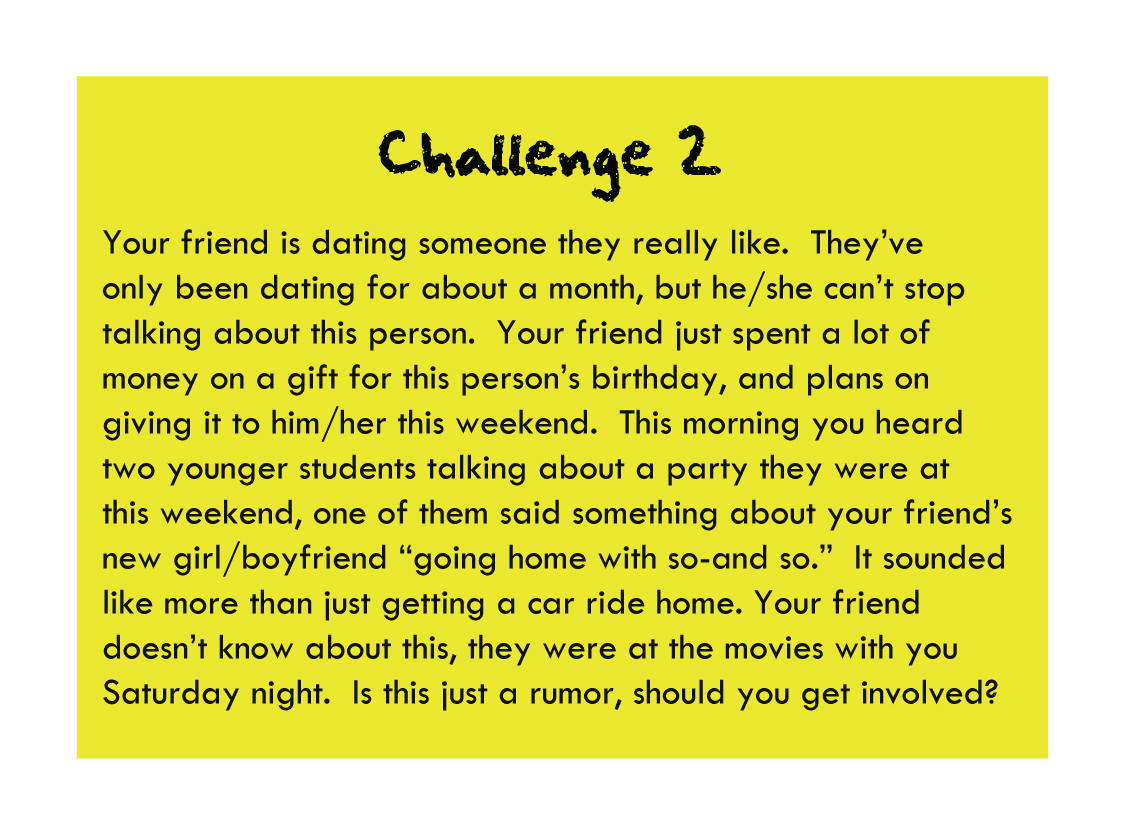

Edtec 670, Exploratory Learning Through Educational Simulation and Games, featured four main projects. Two were highly reflective, where students focused on concepts and trends relating to relationships between games, learning, motivation and fun. Students posted and reviewed video interviews and blog entries through multiple forums. The other two projects were task-based, concept and design projects. We separated into teams with shared gaming interests, and conceived, designed, and in one instance, fully developed an educational game, a concept-to-completion project, culminating in an off the shelf (Internet) packaged product. Our product is The class was large by online course standards, combining the Cohort, Campus and Distance programs into one 2 ½ hour online course, co-taught by Professor Bernie Dodge and Karl Richter. Getting a word (text) in edgewise during class could be a challenge. There was often a lot of active text-messaging on the Wimba board, a typed question would frequently scroll from bottom-to-top and off the screen before either instructor caught it. Timing was crucial. This is where I first developed my Word-to-Wimba technique (w2w). It also illustrates the importance of good communication with teammates. I was lucky, both my partners John Miller and Avni Vyas, were near completing the program and savvy communicators. Challenges & Opportunities I’d not given thought to connecting an Edtec competency to Clean Slate at the time of design, which is ironic because upon reflection I realize the project and product included many of the elements that not only attracted me to instructional design and technology, but inform my goals moving forward. The Edtec Standards definition of Systems describes a major phenomenon that drew me to this field to begin with and aligns well to this particular artifact – consequences. This was an ideal opportunity to explore instructionally, creatively and technologically my interests and skills in this area. I am fascinated by games that interact with the players, where consequences mean more than your score or the number of chips you collect; where choices effect game play, strategy, and possibly require the player to exercise a different skill-set than they may have anticipated at the beginning of the game. These games spur the imagination and challenge us as players and thinkers.This is the type of game I wanted to create, fortunately I was part of an intellectually curious group with complimentary interests. John was a middle school teacher who wanted to focus on content: specifically the challenges posed to kids who attend schools in communities with gangs. Avni was interested in designing a game about values, and cultural sensitivity. Fitting these three together conceptually was the most fun and creative part of the design and development process. I believe some existing skills I’d brought to group were well suited to this phase of design. The execution phase posed greater tests and challenges. Clean Slate is played by groups of students in a classroom with a teacher or counselor as the facilitator. The premise challenges teams with a variety of unpredictable events as they make their way from 6th through 12th grade. These challenges are based on real life situations students currently face in school, with the desired outcomes such as, exercising problem-solving skills, using strategy and resources to negotiate obstacles, and empathizing with a variety of views. To successfully design a game that includes events to support these learning outcomes, one must build multiple consequences into the game. That means, multiple content. We were also challenged to incorporate relevant events and agents that created these opportunities. The greatest challenge for me, was the depth and amount of content we’d set ourselves up for in the conceptual stage. . . .Okay– that I set-us up for. We needed a lot of content. John provided The other great challenge, were the rules of the game These rules were a very close competitor for my Cognitive Artifact. Ultimately, the rules were the issue that kept the game from reaching the elegant phase of design, as noted in our game’s evaluation. It took me some time away from Clean Slate to go back, revisit them and accept that. (I wrote the rules). It’s true. They are inclusive and detailed, but they are dense and read a bit too complex, which means that the game is too complex. Lessons I learned a lot in this process. The consequence of my choices up front created complications on the back end, in terms of amount and depth of content and the over all sheer “weight” of the project. The rules for the game are an interesting metaphor for this experience. I was still tweaking the rules of the game after much of it had been developed to try to get it to fit together. This process, I believe is a very delicate balance within the context of game design and I would liken it to the concept of an iterative evaluation process. I take away from this that some events of instructional design best not play out in a linear fashion, ditto in game design. It may be easier to write the rules up front. If you stick to them your final product will look exactly like what you decided it would, which is fine if you know for a fact that you a) anticipated and solved every potential problem beforehand, and/or b) will not discover better ideas along the way. The opposite, rewriting the rules after the die is cast, forces the designer to bare the weight of a finished product on their back while trying to reset the foundation. Put, another way, its like pulling your pants on after you’ve already tied your shoes. The value of this lesson is that it applies to so many aspects of what we do as instructional designers. It should be noted that John Miller did in fact “Play Test” a prototype of our game with one of his classes, and that did inform some important and timely changes to our design. The takeaway from that is to just do it early and often. |

- Justin Kennedy | 2011 © All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy

- Vinton Ave.

Los Angeles, CA 90034

- Tel.: (323) 555-1212

E-mail: sdsu@justin-kennedy.net